Being an architect, I have a

lot of architect friends. I don’t think

this is atypical. My wife and I went

through architecture school together in the same class. In fact, in our class of 22 graduates, there are 3 couples who got

married. 25% of the people in our class married other people in our class. And they/we are all still married! And, except for my wife and me, both of the

other couples have an architecture business with their spouse. The relationship percentage from our class is

even more perverse if you counted all the relationships that started between

classmates that didn't end in marriage - but that is a totally different story

(and one that has to be much more delicately told).

|

| Where luckier kids than us now go to architecture school at PSU. |

But then I started to think

about all of my former classmates, co-workers and colleagues who finished their

degree and either immediately or eventually left the profession. Or those who still practice architecture but have

a significant foothold in other professions.

Again, from my class of 22, I could immediately think of more than a

handful of people who now make a living doing something other than

architecture. When I think about the

investment we all made to graduate from architecture school, and some of us the

further investment to pass the Architect Registration Examination (ARE) tests

(9 of them when I took them), I began to wonder if it was the profession itself

that spurned recent graduates and forced them to consider other

professions. Or is that architecture

school has the ability to produce people who are capable of doing more than

just architecture?

I am sure that all

professions have their share of ‘defectors’, but I would think they are the exception

rather than a full third of a graduating class as was the case in ours. And it has nothing to do with gender,

really. As much as the architectural

profession laments about attracting women to the profession, the genders in our

class were split nearly 50/50. Of the

eight people that I can count from my original graduating class who have left

architecture, only 3 are women, so from my graduating class, there are more women still in the profession than men.

So where do these people go

and why did they leave? Do they do

something related to architecture or completely unrelated?

I looked to my classmates,

friends and former co-workers for answers.

Of the people I surveyed, two are in the film industry (one in visual

effects and one in set design – no adult film stars that I know of, sorry). One worked as a product designer for a major

ceiling product manufacturer. Two work for the federal government. One works for a large retirement community

and helps new residents layout their new homes and sell their existing

ones. One is a jewelry designer and

sculptor who sells her merchandise in museum gift shops and craft shows all

over the country. One person now

engineers and builds millwork and cabinetry.

One classmate owns and operates a needlework business. Last but not least, one colleague now runs a

catering business and gourmet shop.

Notice there is no stay at home mom or dad listed. While some may have also done this job IN

ADDITION to their other job, it isn't as if these people have picked up their

ball and gone home. They are

contributing to the work place in other ways, some related to architecture,

some not so much.

I thought about this and asked each person I know in this

position to answer a fourteen question survey.

As to be expected, some surveys took a very long time to get back

(architects are notorious procrastinators).

Some I am still waiting on. I

hold no ill will, but they are off the Christmas Card list for sure. Actually we are so bad at getting Christmas

Cards out, we have changed them to New Year’s Cards. Also, I do none of the work on the holiday card

front for my own family.

I tried to get an idea of why each person in the focus group went

into the study of architecture, when he/she felt like they might want to change

professions, how architecture school may have prepared him/her for other

endeavors and if he/she would do it differently or what suggestions might be

useful to those pondering the profession.

In terms of when the decision was made to enter architecture

school, most of the respondents indicated fairly late in high school. I don’t know if that is unusual. My own answer to this question is 7

th grade or so.

One person indicated a very young age (before 10 years old), and two actually

made that decision after college orientation or after a full year of

college. Our class had a high percentage

of students that were older, from 20 to 30 years old, rather than 17 or 18 like the rest of us. I am not sure of the reason for this but it

didn't really matter other than when it came to buy beer. I would guess that the dropout rate for the

traditional freshmen was about the same as those entering architecture school

with a few years under their belt.

When asked if there was any point that they felt entering

architecture school was the wrong one, answers were all over the board. Some had doubts in school (of course we all

did in some way due to the pressures of studio). One person actually left a message for their

adviser in order to start the process of switching majors. The adviser never called back and he ended up sticking it

out (see above for ‘procrastination’).

One woman kept a pink ‘Change of Major’ slip pinned in their work space

every year. Another indicates that every

semester was plagued with doubts.

Several respondents settled into the program as we all did, perhaps

after the first couple of years of indoctrination. And lastly, one man didn't have doubts until

he received his first paycheck and saw the amount of overtime he was working.

When asked if they intended to seek employment outside of

the profession immediately following college, most responded that they sought

traditional work for architectural graduates.

Only one intended to pursue work in a related field (architectural

preservation). Many found traditional

work. Only one person I polled fell into

another profession while looking for traditional work; the video gaming

industry. In fact when he started in the gaming job, he

states five of the six people on his team were either architecture school

graduates or licensed architects.

Only one of the respondents is currently a licensed architect. He left the

traditional office job based on having positive relationships with those in the government he worked with while completing projects with or for them. As a result, he left the private sector to

work for the government agencies he had worked with in the past, more in an

Owner’s representative position for construction projects.

Another former coworker also got a job with a government agency in a field directly related to architecture. But when it became clear that a transfer from his current city was eminent, he found work in another department looking for someone in graphics and web design.

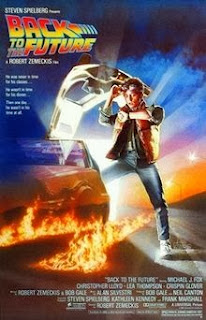

My classmate Jake has a very unique resume. After graduating with us in architecture, he ended up traveling around a bit, trying to decide where to work. In doing so, he passed through San Francisco and thought how cool it would be to work somewhere like Pixar. When traditional jobs did not immediately pan out, he found himself working in the video gaming industry, contributing on several games in the Star Wars series for Lucas Arts and Marvel Nemesis for Nihilistic. Eventually he made his way to the other side of the planet, working for Weta Digital as a Layout Technical Director on films like Avatar, X-Men: First Class, and the Hobbit trilogy. Jake attributes his current skills like spatial layout, 3-D problem solving, art history and managing stressful deadlines to his architectural training.

In

perhaps one of the most unique results of my survey, one respondent actually

came back to work at an architectural office:

the one I work for. Jim had worked for us a

little over ten years ago and eventually found employment with a major

manufacturer of ceiling products, where his wife also worked at the time. He worked in several positions over about a

decade from research and development of ceiling products, to working with

architects and designers to produce specific solutions for their design

needs. While his positions were maybe

more traditionally filled by industrial engineers, the problem solving aspects

of working in buildings perhaps benefited him during his time there. It happened that when I contacted Jim to

answer my survey and catch up for lunch; I gave him a tour of our new office

space. A few weeks later and Jim

rejoined us. Yes our office is that cool.

My friend Melissa runs a business creating handmade jewelry

and other objects made from industrial and recycled materials,

see:

StubbornStiles. She worked in an office for about ten years

before making that move. And if there

were anyone I would have expected to do something outside of architecture, it

was Mel. Not to say she wasn't

talented and couldn't have excelled in an office, but I expected her more than

anyone else I knew from college to create her own professional path. I visited her once in San Francisco many years ago where she

was working in a firm, and it was very strange for me to see her step out of the office

where I met her, dressed the part in every way.

What she does now totally fits her. (She was the one with change of major slip at her desk in college).

My wife worked for a very small architectural firm doing

mostly residential work for a short time, but left to work for a nationally

known home building company. She liked

the residential aspect of the work and she needed to pay off student loans, and

this job was better than where she was.

She went on to move to where I was living in Lancaster, PA (and we still

live there today) and worked for two different regional home builders. She went part time after our first child and

eventually quite all together after our second.

She never fully intended to leave the work force, and continued to work

on some drafting work freelance.

Eventually, an opportunity arose to work through one of her freelance

clients to become what is termed the Transition Specialist for a very large

retirement community. She meets with

clients who will be moving into the retirement community, measures their

furnishings that will be going with them, and lays out the furniture plan for

them in their new apartment plan. She

also provides tips for selling the home they are leaving. It is still a profession very related to

architecture.

I know or know of others that have gone into designing and

building furniture, culinary and catering endeavors, and even a needlework shop

and business. It is clear that all of

these changes in profession have one thing in common: there is still an aspect of design and/or art

relating to them all. When asked how

their architectural education benefited them in their non-traditional

professional field, the answer returned was unanimous from the focus group: the ability to problem solve. It is a different kind of problem solving

than the engineer or mathematician. The

problems presented to architects and even to students in school are open-ended

and never only have one answer. We are

taught to think in terms of options.

Which solution is best for Client A is almost certainly not the best

solution for Client B.

The architect

must work between what the client thinks they need, what the codes require and

what the engineers need to do. I have

always thought that being an architect requires, almost above all others, the

ability to compromise. The best

solutions can answer questions that weren't even asked. Architecture school teaches creative thinking

to spatial problems as well as time management skills. It also teaches how to take criticism. Does it ever…

Most of the people in my limited survey also know others in

their fields who studied architecture or were architects. The last couple of decades have seen a few

deep recessions. Architecture was one of

those majors everyone was warned against very recently,

see:

Degrees to Avoid. Getting a job in architecture has been difficult at several times over the course

of the last 20 years, which can influence some to abandon the traditional route

and go into something else. There are

also several famous folks who at least started an architectural education

before going off to become famous for other things.

See:

Career Paths. Some actually got their degrees and practiced

before going into acting, singing, even royalty…good work if you can find it.

Several respondents suggested they didn't know what they

were getting into. There are a lot of

programs today targeting high school students that didn't exist when I

considered a college major. I actually

have volunteered for the program at Penn State.

See:

Career Advice. This would have been extremely helpful to me

as a college freshman and would have provided for a good transition from high

school to studio. It turns out there are

dozens of these programs over the summer from one week to six weeks.

See:

Summer Programs. I would tend to think that incoming students

at least have the opportunity to know what they are getting into.

Most of the people I polled believe that the education of an

architect, while certainly not completed with a degree, can provide one with a

set of skills that is transferable to other undertakings. Of course to be licensed, there is the

Architectural Registration Exam to contend with, along with the NCARB

internship requirements. But that is a

discussion for another time. Architecture

school is not for everyone, considering my year barely graduated 25% of the

original first year class. Even my

colleagues who are in fields that have college programs tailored specifically

to them (like animation and stage set design) discover aspects of the

architectural program that inform their work.

Needless to say, a Bachelor of Architecture or Masters of Architecture is the most direct path to becoming a practicing architect. But an architectural course of study is able to translate to a wide variety of career pursuits.