Happy Accidents

Serendipity. Providence. Lucky Breaks.

There always seems to be an element of design that is due,

at least in some part, to “fate”. I’m

not talking divine intervention, at least I don’t think so. I’m talking about how, in school, a piece of

your third year model falls off and moves to the other side, where it looks

inherently superior. Or, while

frantically trying to pin up for a critique you flip your trace paper backwards

and your professor makes such a big fuss over the mirrored version, you have to

change the entire trajectory of your project.

Neither of those things happened to me, of course, but I

have seen similar situations. In real

life even.

The first occasion I can recall was when we were designing a

camp for missionaries. This was a

training center for those planning to move overseas for extended periods, so

the decor was intentionally sparse. The

living arrangements consisted of four identical buildings each with twelve

monastic cells arranged around a central living and dining space. The rooms were simple, but generous enough

for two people and each has a bathroom with a shower. While the building design was simple, there

was a concerted effort for sustainability that aligned with the values and

mission of the Owner. This project was

to utilize a geothermal heat source. And

this was 1999 in a little town in Pennsylvania.

This town was so small, it had neither liquor licenses nor a locally

adopted building code. Think the town in

Footloose.

|

| The envisioned Campus |

We were hosting a coordination meeting in our office with

the Owner, all our engineering consultants and the Contractor. A geothermal system of this size requires

space for pipes, pumps and tanks, especially since the campus was going to be utilizing

a well field, shared between these four buildings and the large educational

building on the campus. Our simple parti

did not include large mechanical rooms: basements would be too costly and the

attic arrangements would not accommodate enough space. Do we actually have to build a mechanical

wart on the back of all these buildings?

Problem is, there is no back to these buildings. Half in jest, I said “why don’t we just put

all of it in one of the guest rooms?” It

was about the right size, as it happened.

Crickets.

|

| The chip board model. |

Sorry, just trying to diffuse the tension… Everyone kind of

tilted their heads for a long moment.

After the most pregnant of pauses, the Owner said, “we can make eleven

rooms work in each building.” That was

the solution. Perhaps the most simple

and direct solution there that a room full of people were too focused on to

find. Sometimes it just takes a slightly

sarcastic twenty-something kid to disrupt the thought process. Okay, maybe “slightly” is being generous.

|

| We did indeed turn one of the 12 guest rooms into the geothermal mechanical room. |

|

| Just a glamour shot of the shared living/dining rooms. |

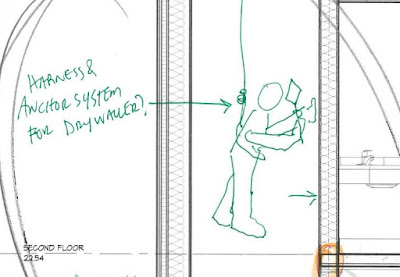

A little later in my professional life, I was confronted

with another situation with which (I believe) I handled with more

maturity. This situation,

coincidentally, dealt with a building housing twelve dwelling units, this time

for retirement living. The rooms were on two floors, six over six, and had

parking below. We had two stair towers

and thought we had them located properly – as many of you reading this will

know, exits must be a certain distance apart to qualify as separated. In this case, one-third of the overall

diagonal of the building. We knew this,

we just failed (up until this point) to account for the balconies – and they

were pretty big balconies. Long story

short, we had to push one of the stairs away from the core of the

building. I felt responsible. I was responsible. Not only was it my job to fix it, but it

was my job to tell the Owner how we had to change their plan.

|

| In the original rendition, the stair was more or less flush with the porches. |

The plan only had to change slightly, but the stair had

to project out farther than previously envisioned. It actually provided for some improved

privacy between two adjacent balconies and created a feature on the rear of the

building. This time there was something

of a back to the building and it needed a feature, and here was the opportunity

to break up the rear elevation and introduce a tower element. Even so, the change would add some square

footage to the program and add some cost and we (that is to say I) still had to

convince the Owner that this would be a good thing. I sat down with the Owner to review the code

issue with the location of the stairs and the proposed solution. Without any hesitation, the Owner latched

onto the new design as an improvement.

No head tilts, no pauses (pregnant or otherwise)…

|

| Without the projection of the stair, I don't believe this elevation would have worked as well. |

This is the 45th topic in the ArchiTalks series where a group of us (architects who also blog) all post on the same day and promote each other’s blogs. This month’s theme is "Happy Accidents" and was suggested by me this month. A lot of other talented writers who also are architects are listed below and are worth checking out:

-->Eric T. Faulkner - Rock Talk (@wishingrockhome)

When a Mismatch isn a Match -- Happy Accident

-->Michele Grace Hottel - Michele Grace Hottel, Architect (@mghottel)

"happy accidents"

-->Nisha Kandiah - The Scribble Space (@KandiahNisha)

Happy Accidents

-->Mark Stephens - Mark Stephens Architects (@architectmark)

There is no such thing as a happy accident

-->Architalks 45 Anne Lebo - The Treehouse (@anneaganlebo)

Architalks 45 Happy Accidents